There have been many studies investigating intermittent fasting in animals and some studies in humans. As yet we don’t have any firm answers about which fasting regimen is best for health, but there are signs that many forms of fasting can bring health benefits.

Studies in animals

Early studies into intermittent fasting were done with animals. Using animals is a good way of ensuring that the two groups (in this case those who are intermittently fasted compared with those who are not) are identical. With humans there are so many other factors that can get in the way like age, previous diet, illnesses, eating habits and so on. Animal studies, therefore, are a good way to start one’s investigations.

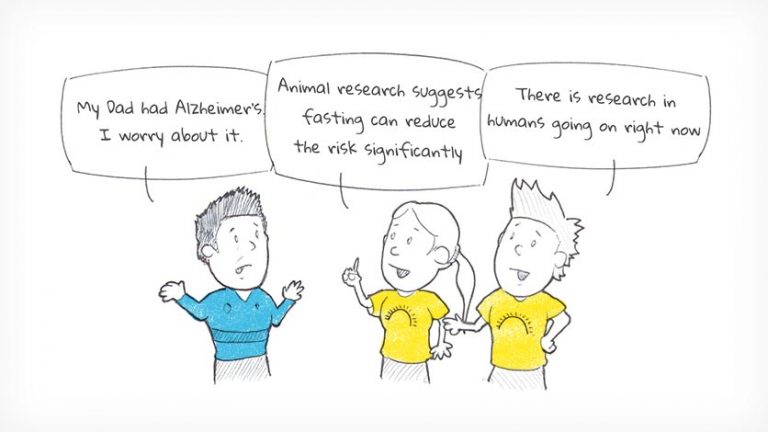

Studies in animals have concentrated on alternate day fasting (ADF).1-19 Improvements in diabetes and factors that lead to cardiovascular disease,1-3,5,6,10 diabetes,5,8,16-18 cancer,4,7,12-15 and neurological conditions5 have been seen, and some studies have found that intermittent fasting leads to animals living for longer than their non-fasted brethren.9,19

These studies in animals all used rats and mice who were fed as normal for 24 hours and then fasted for 24 hours repeatedly in an ADF pattern. Unfortunately, for us humans, when animals such as rats or mice are fasted for 24 hours this does not equate to us fasting for 24 hours. Rats and mice live their lives so much faster, with a much higher metabolic rate, than we do that going without food for a day is like us going without food for a week at a time! This calculation is based on the fact that when humans fast completely it takes about 10 days to lose 10% body weight, it takes rats about 24 hours to lose 10% body weight and it takes mice less than 24 hours to lose 10% body weight, so a 24-hour fast in a rat is like us going 10 days without food, whereas fasting for 2–3 hours for a rat is like humans fasting for 24 hours.

Ideally, to have an insight into the benefits of 5:2 in humans by using animals we need studies where rats are fasted for 3 hours and then fed for 8 hours repeatedly, or for ADF they would fast for 3 hours and be fed for 3 hours. There have been no such studies using this pattern, although some investigations have been done in which animals were fasted for a few hours each day. Unfortunately, the shortest fasting time examined in animal studies is 12 hours which is similar to a 5 day fast for humans. However, like the animal ADF studies, experiments were animals were fasted for some hours daily have also found reductions in body weight and improvements in factors associated with increased risk of cardiovascular and heart disease and diabetes.20

These animal studies are very encouraging but we cannot assume that the benefits seen in animals will translate to humans following an intermittent fasting lifestyle. Luckily, in recent years studies in human have been started.

Studies in humans

There are increasing numbers of studies into intermittent fasting being conducted in humans. So far, most have been done using intermittent fasting for just a few weeks, but even in that short time some great benefits have been seen.

Dr Krista Varady, author of the Every Other Day Diet, has been at the forefront of human studies into intermittent fasting.21-32 In her studies, participants fasted every other day for 8 to 12 weeks, with a 500–600 calorie meal at midday on the fasting days. These studies, performed in overweight individuals, have generally shown improvements in the factors associated with risks of cardiovascular disease and diabetes (weight loss together with improvements in cholesterol, LDL particle size, fasting insulin and glucose and blood pressure). The studies also found that the weight loss was primarily due to loss of fat with little change in muscle mass. When ADF was compared with simple calorie restriction, although the amount of weight loss was similar, less fat free mass (i.e., muscle and bone) was lost with intermittent fasting. Dr Varady is currently conducting longer-term studies into ADF in which participants move on to a maintenance phase in which they continue to fast every other day but eat 1000 calories on their fast days. We are looking forward to seeing the results of these studies and will bring you their key findings as soon as we can.

Two studies of ADF fasting by Heilbronn and colleagues,33,34 were conducted in normal weight men and women in which participants fasted completely on alternate days. These studies found that even in normal weight individuals most of the weight lost was fat, with good preservation of muscle tissue. Importantly, Heilbronn’s study found that in women, but not men, after three weeks of ADF the insulin response to carbohydrates in a meal following a fast was blunted resulting in temporary worsened glucose tolerance. This effect was not noted in Varady’s studies of ADF in overweight women or men in which a small meal was taken on fast days.21-32

A study by Halberg and others35 looked at the effects of fasting for 20 hours every other day for two weeks in healthy men. The participants were instructed to over-eat when they did eat in order to avoid losing weight. The study investigated the effect of fasting on insulin action in normal weight men and found improved insulin sensitivity. As worsened insulin sensitivity (i.e., insulin resistance) is behind so many modern diseases, this is an important finding, particularly since the study was designed to avoid any weight loss. Another study by Soeters and colleagues,36 using the same fasting protocol of 20 hours fasting every other day for two weeks in normal-weight men, found a reduction of activity in a pathway that is used by cancer cells to multiply and keep multiplying longer than normal cells, suggesting that intermittent fasting might reduce the risk of cancer. Again the fact that this was seen despite not reducing calorie intake is important. Interestingly, this study did not find the improvement in insulin sensitivity found by Halberg. Notably the participants in the study by Halberg had a slightly higher BMI (just into the overweight bracket) than in the study by Soeters whose participants all had a healthy BMI, which may have influenced the findings on insulin sensitivity as it is known that diabetes risk increases with increasing BMI.

Dr Michele Harvie and colleagues, have conducted studies on fasting for two days per week37,38 and these formed the basis of the Two Day Diet. In these studies, overweight or obese women ate a low calorie (around 1000 calories), very low carbohydrate (around 50g) diet for two consecutive days per week, followed by five days of a Mediterranean diet. Again, improvements in cardiovascular and diabetes risk factors were seen.

A study in older men (aged 50–70 years) who fasted for two days per week and followed a modest calorie reduction (300–500 calorie deficit per day) on the remaining days39 found improvements in body weight, body mass index, fat percentage, fat mass, blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol. They also found a reduction in markers of damage to DNA which might suggest a benefit for the ageing process. A further publication from this group,40 reported that men following this fasting regime experienced benefits to their quality of life with improvements in tension, anger, confusion and overall mood as well as an increased sense of energy.

There has also been one study by Varady’s group on fasting for one day per week combined with 6 days of reduced calorie dieting.41 This also found similar benefits to the studies of more frequent fasting.

There have been several studies looking at daily fasting with eating only allowed for a restricted time (an ‘eating window’).42-52 Most of these are studies of Ramadan fasting in which food is only allowed during the hours of darkness. In practice, this means about a 12-hour fast during the day with a shorter overnight fast of around 8 hours, combined with two meals: before sunrise and after sunset. The length of the daytime fast during Ramadan varies depending what time of year the month of Ramadan falls. Generally these studies have found that people lose weight during Ramadan,45-52 even though they may actually be eating more calories.47 Most have also seen an improvement in cardiovascular risk factors and blood glucose levels. One study found that Ramadan fasting also seems to reduce inflammation in the body.52 As the meal after sunset during Ramadan is traditionally a time of feasting, the fact that an improvement in health markers has been found in so many studies is fascinating.

One interesting experiment that used an eating window approach focussed on preventing night-time snacking.42 Healthy young men were asked not to eat between 19:00 hours and 06:00 hours (an 11-hour fast) for two weeks. Despite the relatively short fasting time, the study found that simply preventing evening eating resulted in a reduction in daily calorie intake of about 250 calories and a small weight loss.

Read more about different ways of intermittent fasting

Research into intermittent fasting is continuing with studies ongoing in several research centres. Some current research projects include: investigating the effects of intermittent fasting on brain function, the effects of fasting for longer periods less frequently, the effects of fasting for improving the effectiveness and reducing the side effects of cancer therapies, the effects of skipping breakfast on blood glucose in diabetes, the effects of intermittent fasting on markers of heart disease and ageing, and the effects of a 4–9 hour eating window on blood glucose and markers of inflammation.

At FastDay we are constantly monitoring the scientific literature and will continue to keep you informed as and when the results of these studies are published.

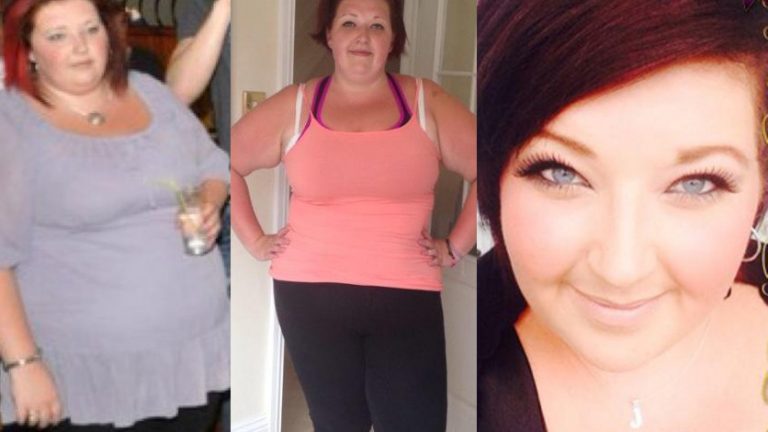

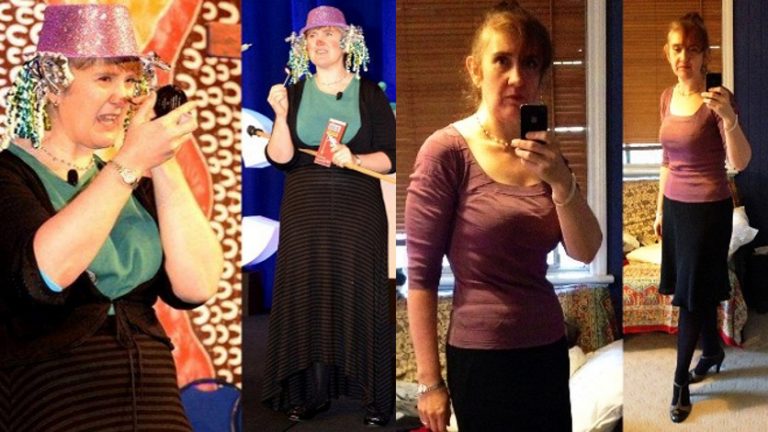

It was only after my sister got to the stage of needing a kidney transplant that the matter of my size came to my attention. The transplant nurse chatted with me about the possibility of my being a donor and of course she needed a few vital statistics – age, height, weight. I could answer the first two on the spot – 40 years, 174cm, but weight? I hadn’t seen a set of scales in years! I dusted them off, stood on them, and got the shock of my life when the figure of 90kg came up. Really??? She hummed and hawed for a few moments and then proceeded to inform me that I was bordering on obese, and obesity could rule me out of being a donor. Eeek! Something had to be done!

It was only after my sister got to the stage of needing a kidney transplant that the matter of my size came to my attention. The transplant nurse chatted with me about the possibility of my being a donor and of course she needed a few vital statistics – age, height, weight. I could answer the first two on the spot – 40 years, 174cm, but weight? I hadn’t seen a set of scales in years! I dusted them off, stood on them, and got the shock of my life when the figure of 90kg came up. Really??? She hummed and hawed for a few moments and then proceeded to inform me that I was bordering on obese, and obesity could rule me out of being a donor. Eeek! Something had to be done! My BMI is comfortably in the healthy range and I’m fitting into my old clothes again. I love the comments that I’ve been getting from work colleagues, but most of all I love the energy that I now have. At the start of the year I was always tired and lethargic, thinking that I was going to have to go see my doctor to have my thyroid checked. Now I have the energy to make it through a busy day and still feel enthused about doing things on the weekend…even chores! The other thing I’ve noticed is that my depressive lows that I periodically go through have been much gentler and easy to manage – that was something I hadn’t expected. I’ve dealt with stresses (and I’ve had many big things come up over the 6 months) much better than I have in the past. I don’t know if fasting is the direct cause of all of it, or whether feeling good about myself has led to a better frame of mind, but all I can say is that I am in a much better place physically and mentally than I had been earlier in the year.

My BMI is comfortably in the healthy range and I’m fitting into my old clothes again. I love the comments that I’ve been getting from work colleagues, but most of all I love the energy that I now have. At the start of the year I was always tired and lethargic, thinking that I was going to have to go see my doctor to have my thyroid checked. Now I have the energy to make it through a busy day and still feel enthused about doing things on the weekend…even chores! The other thing I’ve noticed is that my depressive lows that I periodically go through have been much gentler and easy to manage – that was something I hadn’t expected. I’ve dealt with stresses (and I’ve had many big things come up over the 6 months) much better than I have in the past. I don’t know if fasting is the direct cause of all of it, or whether feeling good about myself has led to a better frame of mind, but all I can say is that I am in a much better place physically and mentally than I had been earlier in the year.